![]()

What People Laugh at and What They Don't

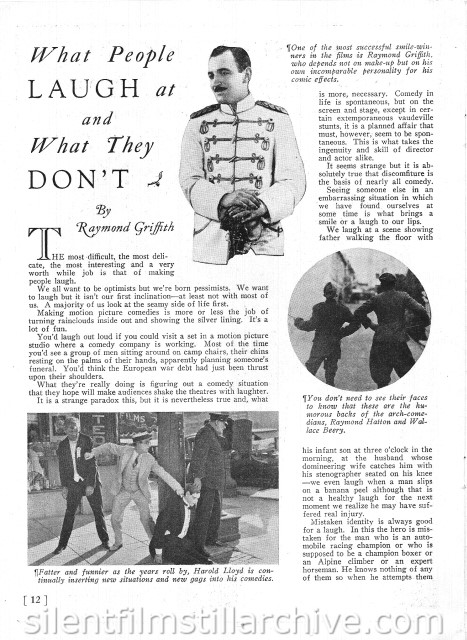

by Raymond Griffith

From THE HOME MOVIE JOURNAL (June,

1926)

Published Monthly by EXETER STREET THEATRE

BOSTON, MASS. Pages

12, 13 and 16

The most difficult, the most delicate, the most interesting, and a very worthwhile job is that of making people laugh.

We all want to be optimists but we are born pessimists. We want to laugh but it isn't our first inclination - at least not with the most of us. A majority of us look at the seamy side of life first.

Making motion picture comedies is more or less the job of turning rainclouds inside out and showing the silver lining. It's a lot of fun.

You'd laugh out loud if you could visit a set in a motion picture studio where a comedy is working. Most of the time you'd see a group of men sitting around on camp chairs, their chins resting on the palms of their hands, apparently planning someone's funeral. You'd think the European war debt had just been thrust apon their shoulders.

What they are really doing is figuring out a comedy situation that they hope will make audiences shake the theatres with laughter.

It is a strange paradox this, but it is nevertheless true, and what is more, necessary. Comedy in life is spontaneous, but on the screen and stage, except in certain extemporaneous vaudeville stunts, it is a planned affair that must, however, seem to be spontaneous. This is what takes the ingenuity and skill of director and actor alike.

It seems strange but it is absolutely true that discomfiture is the basis for nearly all comedy.

Seeing someone else in an embarrassing situation in which we have found ourselves at some time is what brings a smile or a laugh to our lips.

We laugh at the scene showing father walking the floor with his infant son at three o'clock in the morning, at the husband whose domineering wife catches him with his stenographer seated on his knee - we even laugh when a man slips on a banana peel although that is not a healthy laugh for the next moment we realize he may have suffered real injury.

Mistaken identity is always good for a laugh. In this the hero is mistaken for a man who is the automobile racing champion or who is supposed to be a champion boxer or an alpine climber or an expert horseman. He knows nothing of any of them, so when he attempts them - and wins the race or climbs the mountain or wins the fight there are thrills and laughs.

This is the crux of the comedy in Adolphe Menjou's "The Grand Duchess and the Waiter". It was not so frightfully funny to see the meticulous Menjou as a waiter bathing the Duchess' hounds, but Menjou the debonair, man-about-town masquerading as a waiter brought comeday of a rare order to the most menial tasks.

Something close to this is the situation in which the hero accidentally accomplishes a feat, winning a race with a runaway automobile or motorboat on which the control is broken.

Repitition in comedy is very funny at times and other times not. Nothing is more overdone, and nothing is more awful when it is overdone. You can do a stunt just once too often and spoil the whole effect. An assortment of crockery hurled with unerring aim and in quick succession at a fleeing form provokes uncontrollable laughter that increases with every plate that flies, up to a certain point. Beyond that, the situation palls.

It is nothing short of amazing how quickly the audience can sense this. Comedy, in fact, is the most nicely balanced thing in the world. The plot, the actor, the make-up, the direction must all be studied in extreme detail. There is no more difficult task than to write or direct or act in a first-rate rollicking comedy.

Funny situations are always funnier than funny men. A great many of our so-called comedians forget this fact or are totally unaware of it, and the result is the countless stupid comedies thrust at the average movie audience.

A shuffle, a derby, and a cane may rock us with mirth, but not without some situation, however slight, to make the shuffle, the derby, and the cane cease to be mere accessories and become the cause of our laughter.

A pair of tortoise-shell eyeglasses on any of our acquaintances will surely not send us into gales at our friend's expense, yet the sight of Harold Lloyd thus adorned will make countless sides ache.

But Harold Lloyd is not personally "funny looking", any more perhaps than any of our friends - it is rather the absurdity of a situation that heightens the effect of any comic makeup, whether it lies in costume, gesture or facial expression. Any third-rate vaudeville tramp with patched trousers, ruddy nose, and a stock of stale jokes bears ample witness to this.

In most instances the audience likes to be "in" on the plot. Fooling the audience is a fatal mistake. If a man's troubles will be over when he gets the news contained in a certain letter, and he does receive it but one little interruption after another keeps him from opening it, the audience ought to be "in" - to know what's in the letter.

A comedy is not a mystery play. We want to know the gag that is being pulled. It is the privilege of the audience to laugh with the actors at the victim in a comedy. Secrecy and confusion do not excite laughter. The onlooker is too busy trying to figure it all out, unless he becomes downright bored and decides to doze until the photo-play comes on.

We all like what are known in comedy circles as "Bob-ups". If the hero of a comedy pulls a drowning man from the ocean and saves his life only to discover the man is the villain it is good for a laugh.

Cruelty to animals is distinctly out. It is all right for a dog to grab a man by the leg, but the man must not strike the dog.

Comedies must be clean and wholesome. That is very important. We may laugh at the joke of a comedy situation that is off-color, but we don't mean it. The laugh is no more sincere when the cause is the man slipping and falling on a banana peel.

The camera lens shows everything. If the actor is egotistical it shows up as boldly as headline type in a newspaper and we all resent it. He must keep the common touch - he must remember that he is one of the many, many pebbles on the beach.

Last Modified August 24, 2009