![]()

THE COQUELIN OF THE MOVIES

BY HENRY WYSHAM LANIER

The World's Work Magazine, March 1915, pages 566-577.

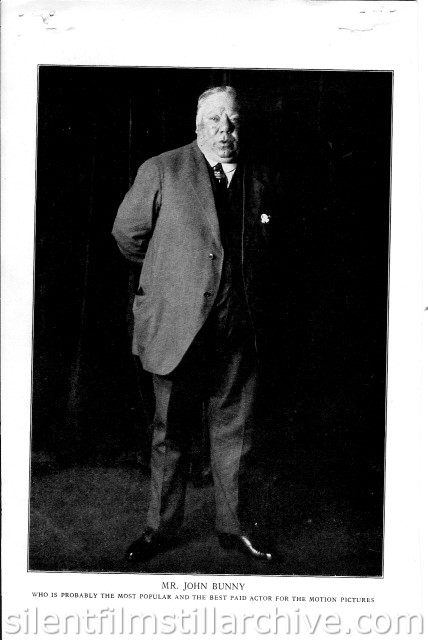

MR. JOHN BUNNY

WHO IS PROBABLY THE MOST POPULAR AND THE BEST PAID ACTOR FOR THE MOTION PICTURES

THE COQUELIN OF THE MOVIES

MR. JOHN BUNNY, WHO GAVE UP AN ESTABLISHED CAREER ON THE "LEGITIMATE STAGE TO BECOME MIRTH MAKER TO THE MILLIONS AND TO DEMONSTRATE THE ARTISTIC POSSIBILITIES OF THE MOTION PICTURES

BY

HENRY WYSHAM LANIER

FOUR years ago there was in the Broadway group an actor named John Bunny. He had started his career before he was of age, as tambo end man in an obscure minstrel show, and had gradually worked up till he had a reputation as a comedian which had put him into the best productions — " supporting" such stars as Maude Adams and Annie Russell, and drawing salaries of from one to two hundred dollars a week. He had even achieved that dream of the comedian who takes his work seriously — of appearing as "Bottom."

So, as things go, he could look back upon a long advance and a distinct success.

But this particular comedian happened to be an exceedingly level-headed person. He noticed around 1910 that not only could he not detect any- very appreciable growth of his personal prestige during the seasons just preceding, but that the stage itself seemed in such a bad way that he was getting less and less chance to show what ho could do or to grow in his own art. This phenomenon has been observed by a good many actors at one time or another; and it was particularly prevalent about four years ago. Cases might be cited where its main effect has been to produce in the actor's mind a conviction of the public's deficiencies, which he has even been known to allude to openly.

Mr. Bunny, however, was temperamentally inclined to do what Hawthorne told Emerson that Margaret Fuller had at last learned: "to accept the world as it is." (The Sage of Concord's reply, by the way, was " My God! She'd better!") Having observed perforce that there was a certain low form of entertainment (as Dr. Johnson says of the drink, porter) called the moving pictures, to which the populace was flocking in a manner that brought tears to the eyes of the "legitimate" managers, Mr. Bunny decided to investigate and see if there could be any connection between these facts.

Accordingly he took a couple of weeks off (it wasn't especially difficult for any actor at that time) and made a systematic round of the motion picture theatres. What he found crystallized his vague ideas into a definite conviction: it was

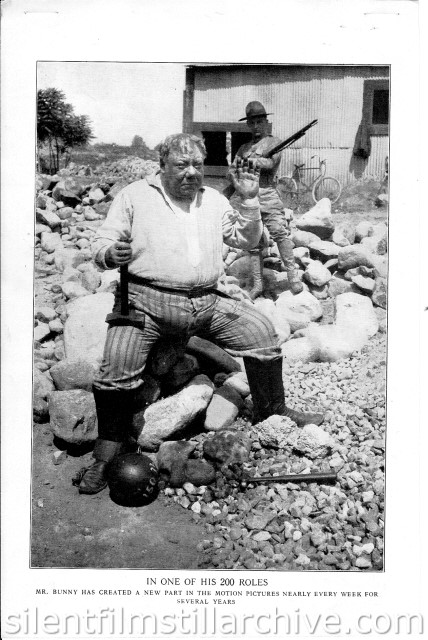

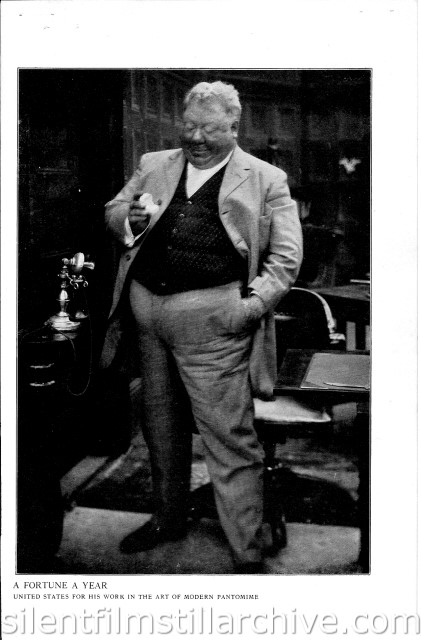

IN ONE OF HIS 200 ROLES

MR. BUNNY HAS CREATED A NEW PART IN THE MOTION PICTURES NEARLY EVERY WEEK FOR

SEVERAL YEARS

A COMIC EDITION OF "THE MAN WITH THE HOE"

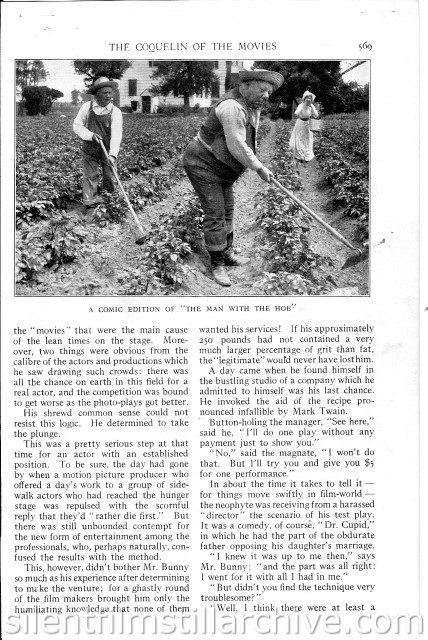

the "movies" that were the main cause of the lean times on the stage. Moreover, two things were obvious from the calibre of the actors and productions which he saw drawing such crowds: there was all the chance on earth in this field for a real actor,-and the competition was bound to get worse as the photo-plays got better.

His shrewd common sense could not resist this logic. He determined to take the plunge.

This was a pretty serious step at that time for an actor with an established position. To be sure, the day had gone by when a motion picture producer who offered a day's work to a group of sidewalk actors who had reached the hunger stage was repulsed with the scornful reply that they'd "rather die first." But there was still unbounded contempt for the new form of entertainment among the professionals, who, perhaps naturally, confused the results with the method.

This, however, didn't bother Mr. Bunny so much as his experience after determining to mike the venture; for a ghastly round of the film makers brought him only the humiliating knowledge that none of them wanted his services! If his approximately 250 pounds had not contained a very much larger percentage of grit than fat, the "legitimate" would never have lost him.

A day came when he found himself in the bustling studio of a company which he admitted to himself was his last chance. He invoked the aid of the recipe pronounced infallible by Mark Twain.

Button-holing the manager, "See here," said he, " I'll do one play without any payment just to show you."

"No," said the magnate, "I won't do that. But I'll try you and give you $5 for one performance."

In about the time it takes to tell it — for things move swiftly in film-world — the neophyte was receiving from a harassed "director" the scenario of his test play. It was a comedy, of course, " Dr. Cupid," in which he had the part of the obdurate father opposing his daughter's marriage.

" I knew it was up to me then," says Mr. Bunny; "and the part was all right: 1 went for it with all 1 had in me."

" But didn't you find the technique very troublesome?"

"Well, I think there were at least a

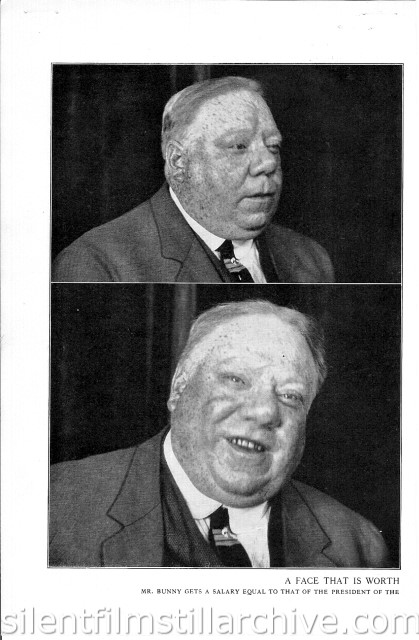

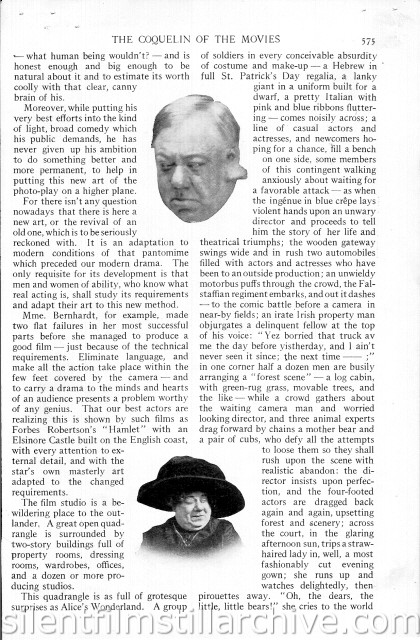

A FACE THAT IS WORTH A FORTUNE A YEAR

MR. BUNNY GETS A SALARY EQUAL TO THAT OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR HIS WORK IN THE ART OF MODERN PANTOMIME

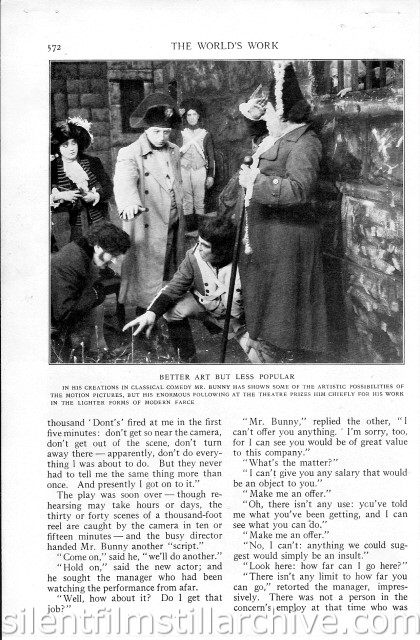

BETTER ART BUT LESS POPULAR

IN HIS CREATIONS IN CLASSICAL COMEDY MR. BUNNY HAS SHOWN SOME OF THE ARTISTIC POSSIBILITIES OF THE MOTION PICTURES, BUT HIS ENORMOUS FOLLOWING AT THE THEATRE PRIZES HIM CHIEFLY FOR HIS WORK IN THE LIGHTER FORMS OF MODERN FARCE

thousand ' Don'ts' fired at me in the first five minutes : don't get so near the camera, don't get out of the scene, don't turn away there — apparently, don't do everything I was about to do. But they never had to tell me the same thing more than once. And presently 1 got on to it."

The play was soon over — though rehearsing may take hours or days, the thirty or forty scenes of a thousand-foot reel are caught by the camera in ten or fifteen minutes — and the busy director handed Mr. Bunny another "script."

" Come on," said he, " we'll do another."

" Hold on," said the new actor; and he sought the manager who had been watching the performance from afar.

"Well, how about it? Do 1 get that job?"

"Mr. Bunny," replied the other, "1 can't offer you anything. I'm sorry, too, for I can see you would be of great value to this company."

"What's the matter?"

" I can't give you any salary that would be an object to you."

" Make me an offer."

"Oh, there isn't any use: you've told me what you've been getting, and I can see what you can do."

" Make me an offer."

"No, I can't: anything we could suggest would simply be an insult."

"Look here: how far can 1 go here?"

"There isn't any limit to how far you can go," retorted the manager, impressively. There was not a person in the concern's employ at that time who was

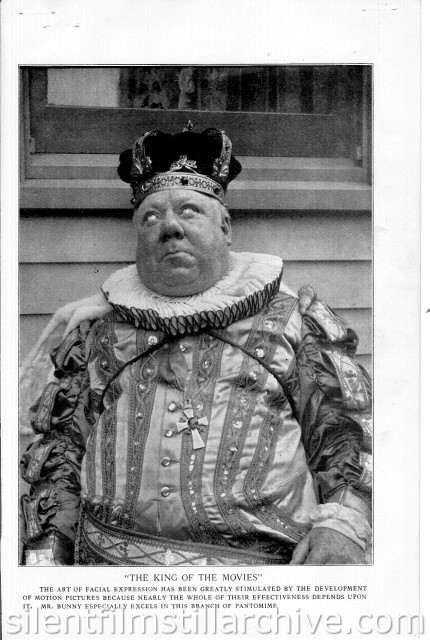

"THE KING OF THE MOVIES"

THE ART OF FACIAL EXPRESSION HAS BEEN GREATLY STIMULATED BY THE DEVELOPMENT OF MOTION PICTURES BECAUSE NEARLY THE WHOLE OF THEIR EFFECTIVENESS DEPENDS UPON IT. MR. BUNNY ESPECIALLY EXCELS IN THIS BRANCH OF PANTOMIME

making half as much as Mr. Bunny's last salary. But this had a rotund and convincing sound.

" Make me an offer," remarked Mr. Bunny.

" But there isn't any use ; we couldn't pay you more than forty dollars a week, and "

"I'll take it."

"Do you really mean it?"

"Sure I mean it. Come on, now, and let me get at that other script."

That was in December, 1910. Since then this concern has put out pretty nearly two hundred Bunny comedies, and the forty dollars a week has grown steadily till it now matches the stipend of the President of the United States — all without any further contract than that conversation with the manager.

I doubt if there are many human beings alive who are known to-day by more people than is John Bunny. Among the hundreds of requests that come for his autograph and picture was one from a Chinese mandarin! And as he was walking along the streets of Paris one day, a distinguished looking old Frenchman suddenly stopped, removed his silk hat, and with a beaming face made him a profound bow: he had recognized the original of a comedy which had delighted him at a "cinema" show. 1 rode with him several miles in his motor through the streets of Brooklyn: every policeman we passed saluted him, with manifest pride and pleasure in the recognition; the newsboys would look up and suddenly the cry would go out: "Yah, Bunny, Bunny! Hello, John!" And the absorbed crowds that filled the street before the baseball bulletins divided to let the car through and then instantly set up a shout: "Bunny! John Bunny! Three cheers for Bunny."

Perhaps some superior person will curl the lip at this "cheap popularity." But 1 declare it's a pretty big thing to have several millions of human beings glad you're living, to have your daily work bring honest, clean fun into the lives of a whole world of men, women, and children.

And the best thing about John Bunny is the way he takes this vast personal popular success: he enjoys it thoroughly

-- what human being wouldn't? — and is honest enough and big enough to be natural about it and to estimate its worth coolly with that clear, canny brain of his.

Moreover, while putting his very best efforts into the kind of light, broad comedy which his public demands, he has never given up his ambition to do something better and more permanent, to help in putting this new art of the photo-play on a higher plane.

For there isn't any question nowadays that there is here a new art, or the revival of an old one, which is to be seriously reckoned with. It is an adaptation to modern conditions of that pantomime which preceded our modern drama. The only requisite for its development is that men and women of ability, who know what real acting is, shall study its requirements and adapt their art to this new method.

Mme. Bernhardt, for example, made two flat failures in her most successful parts before she managed to produce a good film — just because of the technical requirements. Eliminate language, and make all the action take place within the few feet covered by the camera — and to carry a drama to the minds and hearts of an audience presents a problem worth)' of any genius. That our best actors are realizing this is shown by such films as Forbes Robertson's "Hamlet" with an Elsinore Castle built on the English coast, with every attention to external detail, and with the star's own masterly art adapted to the changed requirements.

The film studio is a bewildering place to the out-lander. A great open quadrangle is surrounded by two-story buildings full of property rooms, dressing rooms, wardrobes, offices, and a dozen or more producing studios.

This quadrangle is as full of grotesque surprises as Alice's Wonderland. A group of soldiers in every conceivable absurdity of costume and make-up — a Hebrew in full St. Patrick's Day regalia, a lanky giant in a uniform built for a dwarf, a pretty .Italian with pink and blue ribbons fluttering— comes noisily across; a line of casual actors and actresses, and newcomers hoping for a chance, fill a bench on one side, some members of this contingent walking anxiously about waiting for a favorable attack — as when the ingénue in blue crêpe lays violent hands upon an unwary director and proceeds to tell him the story of her life and theatrical triumphs; the wooden gateway swings wide and in rush two automobiles filled with actors and actresses who have been to an outside production ; an unwieldy motorbus puffs through the crowd, the Falstaffian regiment embarks, and out it dashes — to the comic battle before a camera in near-by fields; an irate Irish property man objurgates a delinquent fellow at the top of his voice: " Yez borried that truck av me the day before yistherday, and I ain't never seen it since; the next time ----" in one corner half a dozen men are busily arranging a "forest scene" — a log cabin, with green-rug grass, movable trees, and the like — while a crowd gathers about the waiting camera man and worried looking director, and three animal experts drag forward by chains a mother bear and a pair of cubs, who defy all the attempts to loose them so they shall rush upon the scene with realistic abandon: the director insists upon perfection, and the four-footed actors are dragged back again and again, upsetting forest and scenery; across the court, in the glaring afternoon sun, trips a straw- haired lady in, well, a most fashionably cut evening gown; she runs up and watches delightedly, then pirouettes away. "Oh, the dears, the little, little bears!" she cries to the world

in general — and "Aren't you a little bare yourself?" queries a fellow professional from a balcony, to her immense delight.

And into this mêlée there walks about quietly, a short, thick-set man, who confesses, 1 believe, to 250pounds, but who is anything but unwieldy. He has a face as surely predestined to make mirth for the world as that of Coquelin. As a writer has described it in the Saturday Review:

"Mr. Bunny has an extensive and extremely flexible face. When he smells a piece of Gorgonzola cheese there is no doubt whatever that his nose has been very seriously offended. When he sees for the first time a pretty and eligible young woman, there is no doubt whatever that he is immensely excited and moved with intentions so extravagantly honorable that they seem almost too grievous to be borne. Mr. Bunny's emotions are all on the grand scale. His despair is incredible. His grief is unendurable. His pleasure can palpably be seen to spread from the ends of his hair to the soles of his feet. His wrath is apoplectic. His terror is the panic of a whole army. His congratulations wring one's hands till circulation is for the moment suspended. We know at once why Mr. Bunny never speaks. He could not possibly find words to convey the extremity of his feelings. It is enough that he should open his mouth."

Yet the most striking thing about this man born to create laughter is a certain dignity which it would take a brave man to outrage: it is quite clear why there are no slap-sticks and no horse play in his productions.

John Bunny is father confessor to half the company; old and young greet him as "Uncle John" and bring him their troubles; the leading lady sits on the arm of his bench and rests her arm about his shoulder; but he manages to preserve this dignity while meeting all comers as hail fellow well met.

I asked him if he didn't find himself handicapped at first in telling the story of a play before the camera without words. "Yes, for a time. But I found the secret was to feel the part I was playing more intensely."

" Did you study your own facial expressions before a mirror?"

"No, no: that's fatal; it makes everything you do hard and unreal. If you can manage to be the character you're impersonating, feel it so thoroughly and vitally that your eally transform yourself for the moment, your actions will tell more than you realize. That is, of course, when you've mastered this particular technique."

A play director walked up. "John, look over this: it's pretty good" — and he handed him a script.

" You must really improvise a great deal," I said, looking at the outline summary of the new play.

"Yes, I have to: here's a situation that leads to this conclusion — often the best method comes of itself. Of course, the time restrictions are very rigid, but 1 find I have the faculty, without thinking about it, of knowing how long a scene will take to work out. 1 can tell at any instant about how many feet of film has been run." "How many real artists are there in regular moving picture work?"

"Well, Max Linder is a great comedian. But outside of him, I'm afraid twenty would be a liberal estimate. But the thing's changing, changing fast. Look at the picture plays of just a few years ago: a moving train was a story then. Now they're filming Les Miserables in twelve reels."

" How about a better grade of plays? I understand most of what the companies

now produce are by unknown authors: isn't there hope for filming some of the great comedies?"

"Listen, I went to England and put in some of the hardest work of my life in producing Mr. Pickwick. I found every place that was unchanged, from Dingley Dell to the White Hart Tavern, and we worked it all out true to life. I'm proud of those pictures — but they haven't sold at all in comparison with these things I'm turning out every week.

" They will, though," he went on. " I'm convinced of that. The public is coming to it. Anyhow, I'm going to do—— this year" — and he named one of the

most delightful creations of a world humorist. "And then — but that's another story; meanwhile I've got to put in twenty minutes over this new script."

I have an idea that the new art of the photo-play is going to owe a good deal more to Mr. John Bunny in the future. He has already shown that a real actor can make an incredible success before this audience without any of the vulgarity or horseplay which used to be considered essential. With the audience itself being constantly recruited from the ranks of the more critical, and with actors of taste and ability, the moving picture of to-morrow is bound to excel even its present wonders.

More Information on Billie Dove...

Last Modified December 30, 2008