![]()

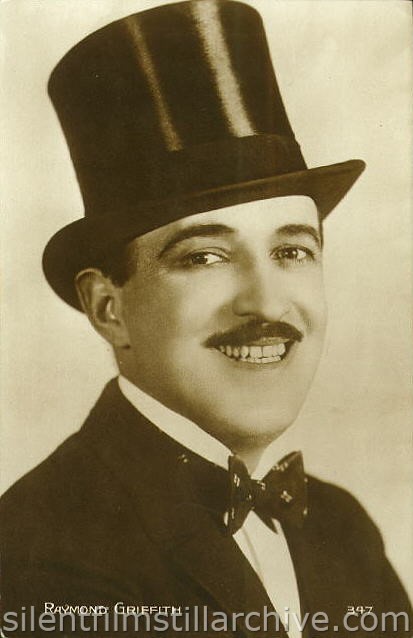

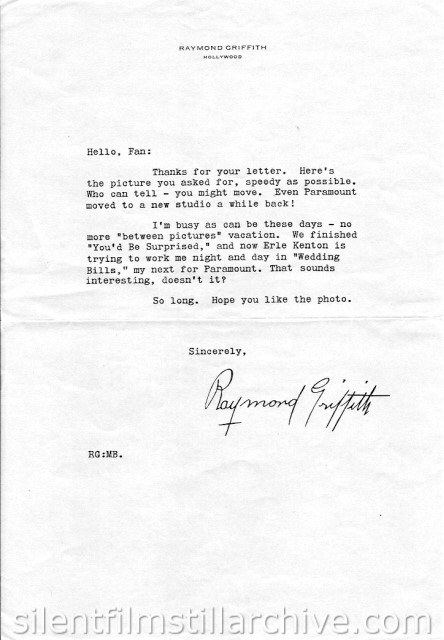

Raymond Griffith

These small publicity photos were sent by Paramount to fans who requested them.

postcard

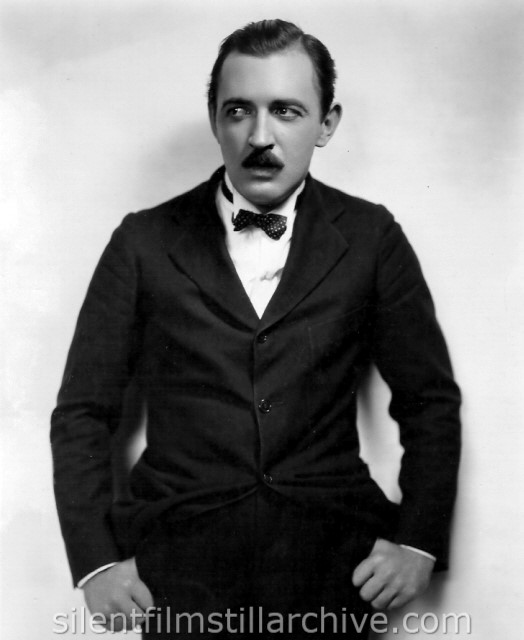

Raymond Griffith publicity photo/drawing

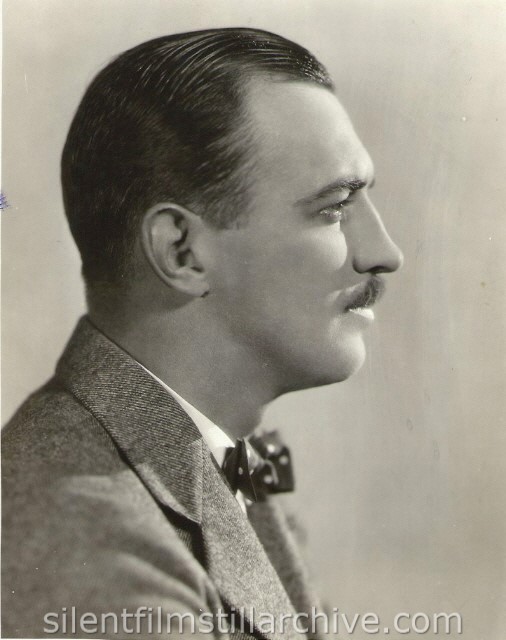

Raymond Griffith publicity photo

Caption: "Raymond Griffith in Goldwyn Pictures. Photographed by Clarence S. Bull".

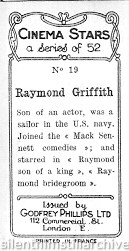

Eurpoean Cigarette card. Cinema Stars, A series of 52, No. 19, Raymond Griffith. Son of an actor, was a sailor in the U.S. navy. Joined the < Mack Sennett comedies >; and starred in < Raymond son of a kind >, < Raymond bridegroom >. Issued by Godfrey Phillips, Ltd., 112 Commercial St., London, E.

Publicity Photo from The Eternal Three (1923)

Postcard from Cinémagazine - Edition, Paris

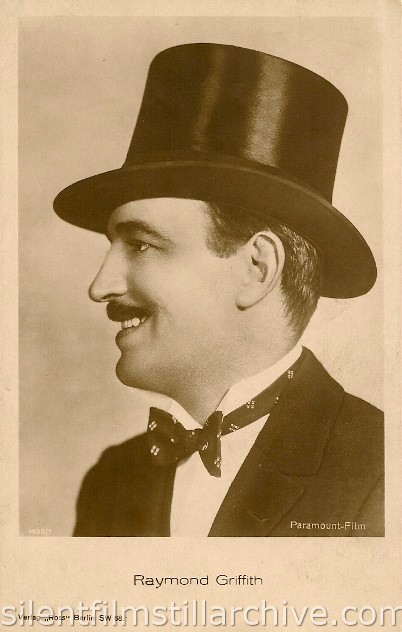

Raymond Griffith

Paramount-Film Verlag "Ross" Berlin SW 68

Raymond Griffith: Silk Hat Comedian

(This article originally appeared in the February, 2005 issue of CLASSIC IMAGES.)

by Bruce Calvert

"Raymond Griffith seems to me to occupy a handsome fifth place - after Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Langdon - in the silent comedy pantheon, a place that is his by right of his refusal to ape his contemporaries and his insistence on following the devious curve of an entirely idiosyncratic eye." - Walter Kerr, The Silent Clowns.

It is testament to Raymond Griffith's talent that he was able to make superior features comedies at all during the 1920s. The "Big Four" comedians (Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Langdon) all produced their best features themselves. They had control over stories, budgets, schedule, and cast selection. Griffith was a contract player at Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount. While Chaplin made one film every three years and the others appeared in only two features a year, Griffith appeared in six Paramount features in 1925, plus an independent production that had been filmed earlier.

A problem with assessing Griffith's status among the greatest of silent comedy is the availability of his films. Many of the films that he starred in have been lost. Only two of his best comedies, Hands Up! (Paramount, 1926) and Paths to Paradise (Paramount, 1925) are available on video. A few of his supporting roles can also be seen on video, but much of his best work is lost or locked up in archives.

Griffith's character was markedly different from any other comedian's at the time. His costume was usually a top hat and tuxedo. He was always grinning; his characters were very cunning. Every situation was another game where he had to try to figure out how to save his hide.

"The things that happen to a man in a soft hat may be humorous or tragic, as the case may be; the same things happening to a silk-hatted individual are excruciatingly funny . . . Why? I don't know exactly. Maybe because it is incongruous. Maybe it is because we have a prejudice against snobbishness or the qualities the silk hat suggests." - From an interview by Selma Robinson called "Under the High Hat", in The Motion Picture Magazine.

Griffith was born into a theatrical family on January 23, 1895 in Boston, Massachusetts. (Most obituaries incorrectly listed his birth year as 1890 or 1897). His father, James Henry Griffith, was an actor from San Francisco, California. Mary Guichard, his mother, was a stage actress who was born in France. Griffith's grandfather, Gerald Griffith had also been an actor, as was his great grandfather Thomas Griffith.

According to his official 1927 Paramount biography, he was fifteen months old when he made his stage debut, playing a baby in his parents' stage company. When he was seven years old, he starred as Little Lord Fauntleroy. He even played "the little girl" in a production of Ten Nights In a Barroom at the age of eight.

"He has a great distaste for the usual publicity given to film actors, and whenever he is interviewed he will not take any hints that he should divulge the truth about how he lost his voice. It is rumored, however, that it was while singing in vaudeville some years ago he contracted a cold which left him with the ghost of a voice, a husky whisper, carrying only a few feet." - Picture Show, Nov. 7, 1925.

Griffith's cousin Jeanette Swift has revealed that he contracted respiratory diphtheria as a child. Although virtually unknown in the western world today, diphtheria was a common childhood disease until a vaccine wiped it out. The diphtheria bacterium can enter the body through the nose or mouth. A membrane will form over the throat and tonsils. If untreated, this disease can be fatal or cause paralysis. In Griffith's case, diphtheria permanently damaged his vocal chords.

At some time in his childhood, Griffith spent some time working in a circus. He later joined a French pantomime group and toured Europe. He also found a job dancing in vaudeville shows.

In January 1910, Griffith enlisted in the Navy. He was about to turn 15 at the time, but he claimed that he was 18 and the Navy accepted him. He served for two and a half years on five different ships before being discharged.

Griffith's Paramount biography says that he started his film career in 1916. He got a job as an extra at Vitagraph in New York. The "leading man" of the film recognized him and introduced him to the director, who gave Griffith a larger part: "Sometime later, a director Wolbert, now dead, saw Griffith in this picture, decided he had the qualities of a good comedian and engaged him to play in L-KO (Lehrman Knock-Out) Comedies".

Actually, Griffith appeared in many L-KO comedies starting in 1915. Paolo Cherchi Usai of the George Eastman House archive compiled a Vitagraph filmography up to 1916 and he did not find any credited appearances of "Ray Griffith" or "Raymond Griffith". There was a Vitagraph director named William Wolbert who died of pneumonia in 1918. However, Wolbert only worked for Vitagraph studios, and L-KO released through Universal.

Griffith made many short comedies at L-KO, most of which were directed by Henry "Pathe" Lerhman. In March of 1916, he left L-KO and went to Mack Sennett's studios at Triangle. He apparently only appeared in five comedy shorts there, and usually in a supporting role. Sennett says in his biography that he would not give Griffith many roles because he thought that Griffith was not funny. Actually, the problem was that Griffith was just not a cartoon-style comic in the Ford Sterling or Mack Swain tradition.

Frustrated, Griffith left Sennett's studio for a short time and appeared in one comedy for Fox, An Aerial Joy Ride (1917). Sennett claimed that Griffith quarreled with the director and left the Fox studios after this one film.

Harry Aitken, the president of Triangle, needed one-reel comedy shorts to distribute with his features, so he produced a series called "Triangle Komedies". Sennett soon pulled out of the Triangle alliance, but Griffith stayed and appeared in over a dozen of these one-reelers. One of these, His Foothill Folly (1917) was sold in 8mm by Blackhawk films in the 1970s. Most of the rest are lost.

In 1918, Griffith was able to get back on the Sennett lot, but he had a difficult time convincing Sennett to put him in a short comedy. Griffith started paying a studio janitor ten cents to laugh at him whenever Sennett was around. Sennett was not fooled by the ruse, but he was impressed that Griffith was sly enough to think of this. Sennett called Griffith into his office and they went over the story for a comedy. When they were finished, Griffith asked Sennett what kind of costume that he should wear.

Sennett later recalled that he said, "I don't even remember your makeup. I can hire actors and directors by the dozen. You're more valuable to me as a writer. I can take property men and make directors out of them, but where in hell can I get writers? You can't buy brains - they're not for sale. You've got to find them and bring them in." So Griffith became a gagman, writer, and assistant director. He even co-directed a short, The Village Chestnut (Sennett, 1918). On Sennett shorts and features, he worked in a team with Johnny Grey and Albert Glassmeyer . . .

"The Griffith-Grey-Glassmeyer team worked in this manner: Griffith composed the story. Glassmeyer brought in gags, old and new, and Grey titled the comedies. After they had agreed on a story-line, Griffith acted as spokesman, and recited it to Sennett. He was highly successful in this role. He acted out the plot, and emphasized the gags by writhing with laughter, crouching, leaping and bucking beneath the load of mirth." - Father Goose, the Story of Mack Sennett.

Griffith probably worked on many shorts and features at Sennett in 1920 and 1921. Unfortunately, the Sennett films of this period do not have any writing credits, so it is impossible to know which films he penned. He also worked as an assistant director on the Ben Turpin featurette Married Life (Sennett, 1920).

Griffith had a reputation as a practical joker. For Johnny Grey's fiftieth birthday, Griffith paid some workmen to disassemble a ten-horse plow and reassemble it in Grey's living room. On the other hand, he also kept a big library of books and loved to read. This probably made up for his lack of a formal education.

Griffith next left Sennett and worked with former L-KO and Sennett alumnus Reggie Morris on a comedy series that was not financially successful. When Griffith was a bigger star, these shorts were later edited together into a feature called When Winter Went (1925).

In 1922, Griffith moved to Marshall Neilan's independent studio. Fools First (Associated First National, 1922) was the first of several crime melodramas that would feature Griffith as a supporting player. The next year, Clarence Badger directed him in Red Lights (1923), a semi-serious mystery film. Badger was another Sennett alumnus who would later direct two of Griffith's finest comedies. Griffith also played himself along with many other celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin, King Vidor, Erich von Stroheim, and Marshall Neilan in the melodrama Souls for Sale (Goldwyn, 1923).

In 1922, Griffith was one of the leads in a serious drama called White Tiger (Universal, 1923). Griffith and Priscilla Dean play two crooks who import a mechanical chess player and use it to gain access to rich people's homes. The convoluted storyline has the two discovering that they are brother and sister, and that their partner, Wallace Beery, has murdered their father. Famed director Tod Browning was having problems with his alcoholism at the time, and producer Irving Thalberg was disappointed with the resulting film. Universal kept the film on the shelf for a year before releasing it. It received poor reviews. (Tod Browning was not allowed to direct The Hunchback of Notre Dame [Universal, 1923], because of this film's failure.)

"When he left Sennett . . . he was a master mechanic of comedy. He could gag. He could time his business to a second. He knew to an inch how much footage a scene should have to get the biggest laugh. In addition to being an actor, he was qualified as a director and scenario writer. His attitude toward the art of screen comedy is that of the mathematician. There is no emotion about it, he will tell you; it is pure mathematics." - Herbert Howe in Photoplay, 1925.

In 1923, actor Douglas MacLean decided to start producing his own features. Griffith supplied the screenplay for the first film, Going Up (Associated Exhibitors, 1923), which was a success. While working for MacLean, Griffith wrote the screenplay for The Yankee Counsul (Douglas MacLean Productions/Associated Exhibitors, 1923) and supplied the story for Never Say Die (Douglas MacLean Productions/Associated Exhibitors, 1924). Griffith is also mentioned has having assisted Thomas Ince with some film stories.

In 1924, Griffith began working as a Paramount contract player. He was always a supporting player, but had a knack for stealing the movie from its "bigger" stars. In Changing Husbands (1924, Paramount) he plays the befuddled husband of Leatrice Joy, who played a dual role as a bored wife who changes places with a look-alike actress. In Open All Night (Paramount, 1924), he supports Adolphe Menjou and Gale Henry as the "next movie sheik" - a parody of Rudolph Valentino. Griffith steals the movie as a drunk with comedy scenes every few minutes.

In Miss Bluebeard (1925, Paramount), Griffith was second-billed to comedienne Bebe Daniels. "Mr Griffith has the comedy role of the Honorable Bertie Bird, who loves to sleep, and is constantly being drawn into other persons' affairs and made very uncomfortable. He makes the spectators roar with laughter when he tries to imitate a cat." - Mordaunt Hall, The New York Times, January 28, 1925.

Paths to Paradise (1925, Paramount) was his first big hit as a comedian. In this tightly plotted comedy-mystery, Griffith plays "The Dude from Duluth". He is paired with Betty Compson as con artists who try to steal a big diamond from both its owner and then each other. Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times liked this film so much that he reviewed it twice in one week!

"Ray and I were dear, close chums off stage. He was a very determined, very ruthless, very shrewd fellow. His big failing as a comedian, which I pointed out to him, was that he didn't know the difference between comedy, travesty, farce, or light comedy. He'd mix it all up. And he would never be the butt of any joke. Now the success of almost all great comedians comes from being the butt of jokes. Griffith was too vain for this. He would get himself into a problem, and then he'd want to think himself out of it. This worked well for a few pictures, but it wasn't a solid basis." - Veteran comedy director Edward Sutherland, who directed Griffith in A Regular Fellow (1925, Paramount), from Kevin Brownlow's The Parade's Gone By.

Hands Up! (1925, Paramount) is touted by most critics to be Griffith's best film. He plays a Southern spy during the American Civil War who tries to divert a gold shipment that the North desperately needs.

A scene from this film illustrates Griffith's style of thinking his way out of a situation. Captured as a spy (probably because he is still wearing his tuxedo), Griffith is stood up at a wall to be executed by a firing squad. A woman with a large basket accidentally walks by. Griffith says via a title "Pardon me, this is a private execution." She drops her basket and runs away in horror. Naturally, Griffith picks up her basket and runs after her to give it back. Dragged back to the firing squad, Griffith slips a plate out of the basket. When the captain gives the order to fire, Griffith flings the plate into the air. Naturally, the soldiers shoot at the plate. Perturbed, the captain gives another order to fire. Another plate flies into the air, and the soldiers shoot at it again. Griffith applauds his own firing squad for their accuracy. The captain draws his revolver. Griffith holds a plate to his side, and the captain shoots it into pieces. Griffith somehow convinces the captain that he can do better. He is aiming the captain's revolver at the captain, when the rest of the soldiers come to their senses and recapture him. When we next see Griffith, he is tied up with his face to the wall and a plate prominently stuck on his back.

In late 1925, Griffith started having problems working with Paramount. Several Griffith films were announced to the press, but were never filmed. Griffith apparently did start working on The Waiter at the Ritz which was directed by James Cruze (The Covered Wagon). However, Cruze was sued for breach of contract by Paramount, and the film was never completed.

Griffith decided to break his contract with Paramount in 1927. In a letter to Adolph Zukor, he begged to be released because he was having a hard time dealing with studio pressures. This decision nearly killed his career. Paramount barely promoted his last films, Wedding Bill$ (1927) and Time to Love (1927). Both of these are now lost films.

On January 8, 1928 Griffith married an actress named Bertha Mann. She was a stage actress who had appeared in at least one silent film, The Blindness of Divorce (Fox, 1918). She would appear in several talkies in the early 1930s. Griffith had first seen her in a stage production on Broadway about ten years earlier. After the performance, he went backstage to meet her. They began a long distance relationship. He would travel to New York to spend time with her, or she would visit him in Los Angeles. For their honeymoon, the couple traveled to Europe for several months. Before they left, Griffith told Photoplay that he was going to England to make comedies for a British firm. No job offers developed from this trip.

Variety reported on November 7, 1928 that Griffith was to sign a contract with Hal Roach to make musical comedies. Unfortunately, the deal fell through. Griffith also was supposedly under contract with Howard Hughes, but nothing came from this deal either.

Griffith was to make one more silent film. His friend, Howard Hawks, would direct it. However, Trent's Last Case (Fox, 1929), would turn out to be a fiasco. In fact, Hawks considered it the worst film that he ever made . . .

"[It] was one of the great detective stories of all time. The only trouble was we had Raymond Griffith as the star and he talked like this [in a hoarse whisper due to damaged vocal cords]. We had it all written for dialog because I thought it would be cute to have him say, "Now I want you to do this . . ." The day we started shooting, they said, 'It's got to be a silent picture. We can't have him talking like this.' The picture never showed anywhere. We turned it into a gag comedy." - Howard Hawks in Hawks on Hawks by Joseph McBride

In his distaste for the film, Hawks glossed over some of the facts. If Griffith's voice was really the problem, then the studio would have just recast the part. Hawks's biographer Todd McCarthy reveals the real reason that the film was shot as a silent. The studio's legal department had only secured the silent-film rights to the novel that was the basis of the film. If they wanted to make a "talkie", they would have to pay more for the rights to record the dialogue from the book. Hawks had already filmed a "part-talkie" and was probably frustrated at making a silent film while the rest of Hollywood was experimenting with sound. "We just kidded the thing . . . we just had fun with it. I don't know anyone who ever saw it, because talking pictures took over right then and there."

Published reports claim that Trent's Last Case was never shown commercially or to the trade press in the United States. But now that industry trade magazines are online, it was reviewed in several magazines. I have also found newspaper listings where it was screened.* It was shown in Great Britain in September of 1929, where it received terrible reviews and was a flop. This film was thought to be a lost film until a print of it turned up in Alaska in the 1980s - much to the chagrin of Howard Hawks.

Griffith finally broke into sound comedies at Al Christie's studio. He signed a contract to make a dozen two-reel comedies. However, he filmed only two shorts there, Post Mortems (1929) and The Sleeping Porch (1929).

Raymond and Bertha wanted a family, but their first son Raymond Griffith, Jr. was stillborn on June 6, 1929. On July 16, 1931, Bertha gave birth to Michael Griffith. In 1933, they adopted a baby, Patricia. Patricia's birth parents had died in an automobile accident when she was an infant.

Griffith's final film role turned out to be his best-remembered one. In Lewis Milestone's All Quiet on the Western Front (Universal, 1930) he played Gerard Duval, a French soldier in the foxhole. In a poignant scene, he is killed by Lew Ayres' character Paul Baumer. As Duval lays dying, Baumer realizes the horror of the war. Griffith's wordless cameo performance was a highlight of the movie. Universal studios used a new high-camera crane to film many of the battle scenes, including Griffith's scene. The film won the Academy Award for best picture of 1930.

It was just a "bit" and the company felt it couldn't afford to pay anything like the customary Griffith salary. Director Milestone and Griffith have been friends for years and 'Millie' had told Ray about the part one Sunday afternoon at Jimmie Gleason's house. Of course, Ray had read the book, and was immediately crazy to do the part. He saw in it not only a chance to do a great piece of work, but being violently opposed to war, he also saw an opportunity of helping to make the picture a great anti-war document.

"So Ray told Junior Laemmle that he would play the part for nothing and forthwith started raising a beard . . ." - "He Got No Pay for Genius" , Photoplay, July 1930.

By 1931, Griffith was already well known as a "script doctor". He was credited with rewrites on five films that year. Four of these jobs were at Warner Brothers, and mogul Darryl Zanuck took Griffith under his wing. In 1932, Griffith was promoted to the job of associate producer. He produced several films at a time, including notable titles such as Three on a Match (1932, Warner Brothers), 20,000 Years in Sing, Sing (1933, Warner Brothers), and Tiger Shark (Warner Brothers, 1932), which was directed by his friend Howard Hawks.

Zanuck left in 1933 for 20th Century Pictures, which was soon merged with Fox. He brought Griffith with him. Here Griffith produced films starring Shirley Temple, Sonja Henie, the Ritz Brothers and many others. Among the important films that he produced were Heidi (1937, 20th Century Fox), Drums Along the Mohawk (1938, 20th Century Fox) and The Mark of Zorro (1940, 20th Century Fox). He and Zanuck were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture for The House of Rothschild (1934, 20th Century Fox).

"Raymond Griffith was the associate producer. He was a very good comedian in silent pictures, but his vocal chords had been injured, so he could barely whisper. He was a good friend of [Darryl] Zanuck, and to help him along, Zanuck made him an associate producer. And he was fine. He understood pictures because he'd been in them and knew all the problems. And he was excellent at gags, suggesting bits and stuff during the preparation. We seldom saw him on the set. But he had an effervescent attitude and we were able to get the story to bubble. It could have been a very heavy-footed thing, but it turned out all right." - Allan Dwan, in Allan Dwan , by Peter Bogdanovich, on Heidi (1937, 20th Century Fox)

The Darryl Zanuck papers at the Lilly Library in Indiana have a memo from Griffith concerning The Littlest Rebel (1935, 20th Century Fox). Griffith suggests a better ending for the film, and warns "if you ever even suggest that Shirley Temple was the inspiration for the Gettysburg Address, they'll throw rocks at us." Griffith did not receive any credit for his contributions to this film, and it is likely that he made contributions to many Fox Films of the 1930s.

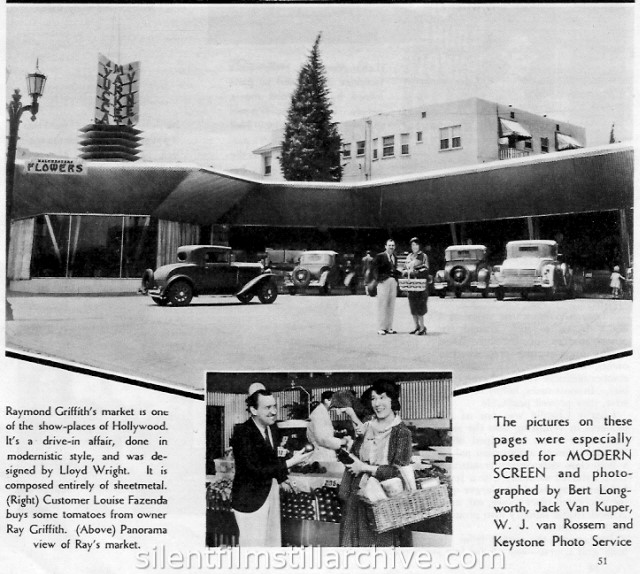

Lloyd Wright, the son of famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright, was a good friend of the Griffiths. Los Angeles records show that Wright designed the Yucca-Vine Market, a drive-in grocery store that was owned by Raymond Griffith. The building was erected in 1930 for a cost of $9000. Unfortunately, this modernistic sheet-metal building has been torn down.

Raymond and Bertha also hired Wright to build them a ranch-style house. Their Canoga Park, California, house was featured in the June 1938 Architectural Forum. The main floor was above ground, but there was also a lower floor with a servant's quarters, wine cellar, play room, and three-car garage and a large swimming pool. In a time when most people did not have any air conditioning, the Griffith house had three air-conditioners and their house was divided into three climate zones.

Griffith was interested in painting and sculpting as a hobby. In 1937, LIFE magazine sent Thomas Hart Benton, a famous American painter, to Hollywood to document the "movie" business. Griffith allowed Benton to sit in on story conferences and screenings at Fox. Benton's Movie Set Cameraman painting was a result of this collaboration. Griffith also loved classical music and opera. He often took his daughter to see musicals and operas at the Hollywood Bowl.

Griffith retired in 1940. He had begun to grow apart from Bertha, and he had an extramarital affair. Although they decided not to separate for the sake of their children, Griffith's daughter Patricia says that her mother never really forgave him. Also, Patricia believes that her father had a nervous breakdown shortly after he admitted the affair.

On the evening of November 25th, 1957, he was having dinner at "The Masquers Club", a private club for actors and producers in Los Angeles. He was dining with two friends when he choked on some food. At first it appeared that he had died of a heart attack, and his obituaries list this as the cause of death. An autopsy was performed on November 27 and it was determined that he had choked on his food and died of "asphyxia".

Bertha lived until 1967. She died on December 20, 1967 from pneumonia. Raymond and Bertha are buried side-by-side at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, Los Angeles.

Griffith's prints on the Hollywood Walk of Fame are in Block 17 at 6100 Hollywood Boulevard.

© Copyright 2004 by Bruce Calvert

Sources: The Silent Clowns by Walter Kerr; The Great Movie Comedians , by Leonard Maltin; American Silent Film Comedies , by Blair Miller; Kops and Custards , by Kalton C. Lahue; Hawks on Hawks , by Joseph McBride; Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood, by Todd McCarthy; Movies of the Thirties , by Ann Lloyd and David Robinson; Dark Carnival , by David J. Skal and Elias Savada; Douglas MacLean: The Man With the Million Dollar Smile by Eve Golden, Classic Images, April 1997, Allan Dwan , by Peter Bogdanovitch; The Parade's Gone By, by Kevin Brownlow; Lost Films by Frank Thompson; Another Griffith by Davide Turconi in Griffithiana, October 1991, Inside Warner Brothers by Rudy Behlmer; Film Notes by Eileen Bowser;The New York Times, July 5, 1925, VII 2;1; The New York Times, June 30, 1925, 14:3; The New York Times, January 28, 1925; "As We Go To Press", Photoplay October 1927; State of California Death Certificate for Raymond Griffith.

*Revised in 2024.

Raymond Griffith's market is one of the show-places of Hollywood. It's a drive-in affair, done in modernistic style, and was designed by Lloyd Wright. it is composed entirely of sheetmetal. (Right) customer Louise Fazenda buys some tomatoes from owner Ray Griffith. (Above) Panorama view of Ray's market.

The pictures on these pages were especially posed for MODERN SCREEN and photographed by Bert Longworth, Jack Van Kuper, W. J. van Rossem and Keystone Photo Service.

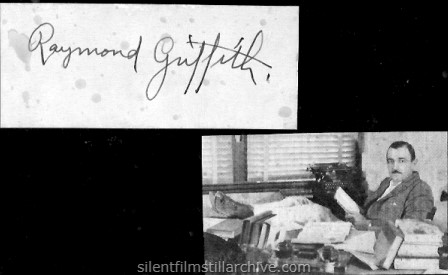

Raymond Griffith's autograph. If you compare it to the "signed" fan photos at the top of this article, you will see that the studio had someone else sign those photos.

Producer Daryl Zanuck, producer Raymond Griffith, producer Lucien Hubbard, and (?) Whyte on the polo field in 1931.

Photo by Irving Lippman

Warner Bros. and First National

AT HOLLYWOOD BOWERY PARTY.

The Gay Nineties' influence has at last reached the party stage. At the

"Old Bowery" party given in Hollywood by the Daryl Zanucks and William

Goetzes, numerous film celebrities appeared in ancient and

laugh-provoking costumes. Among them, were left to right: Harry Green,

Gene Markey, Joan Bennett, Raymond Griffith and Mrs. Griffith (Bertha

Mann).

October 9, 1933

Associated Press Photo From Chicago

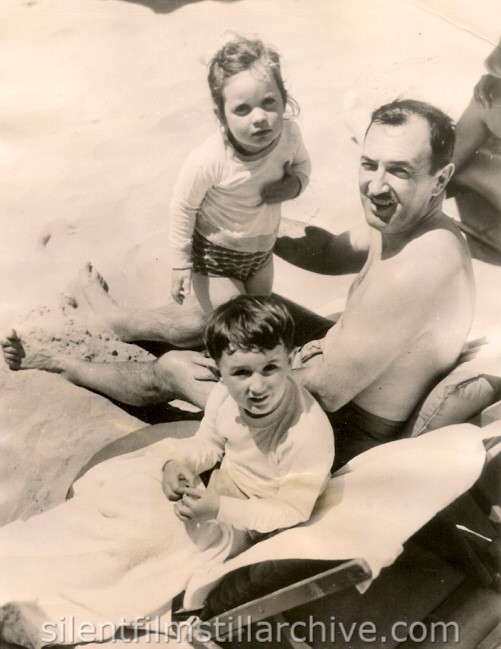

Raymond Griffith, veteran film actor and director, and his children,

Michael and Patricia, are the advance guard of this year's army of film

vacationists at the "American Riviera" at Waikiki Beach, Honolulu

ACTRESS AND FILM STAR TO BE MARRIED. Bertha Mann, stage star, and Raymond Griffith, movie actor, file application for marriage license in Los Angeles. This photo is dated January 27, 1928.

MOVIE STAR RETURNS

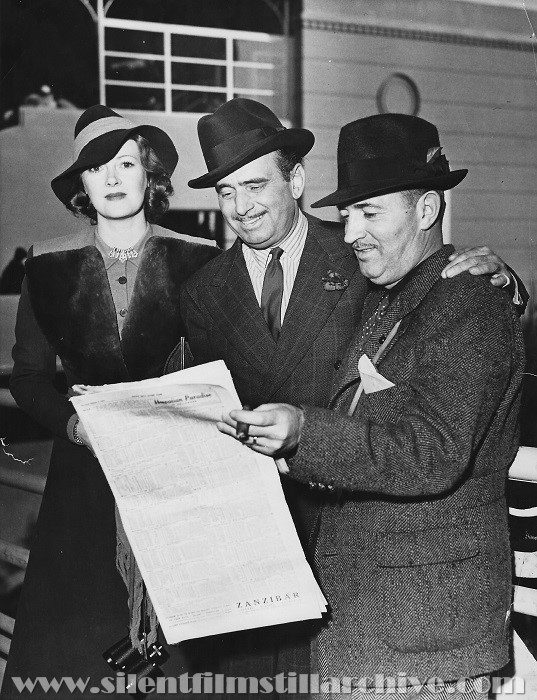

NEW YORK -- Raymond Griffith, one time movie star with his wife, arrive in the United States on a business mission. Mr. Griffith is now directing cinema productions abroad, and will return to the continent shortly. (April 16, 1934)

Paramount publicity photo by Eugene Robert Richee

Congratulations to Harry C. Arthur, Jr., and a long and happy life to his slogan "THE MAGIC SIGN OF A WONDERFUL TIME". Raymond Griffith, Paramount star, and Frank Tuttle, Paramount director, add their names to the long list of people who are wishing Mr. Arthur's playhouses unbounded success.

Harry C. Arthur, Jr. was the president and general manager of Pacific Northwest Theaters (a theater chain). "The Magic Sign of a Wonderful Time" was their slogan for the 5th Avenue Theater in Seattle, Washington (and likely other theaters that they owned also.) Many times movie stars would pose for publicity photos plugging local theater chains. -- Bruce

FILM NOTABLES SNAPPED AT SANTA ANITA

ARCADIA, CALIF: PHOTO SHOWS: L-R

-- Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, (Lady Ashley); Douglas Fairbanks and Raymond

Griffith, film director, who were among the many film notables attending

the races today at Santa Anita. 1/8/38

More Information on Raymond Griffith...

Raymond Griffith's Birth and Death Certificates

Raymond Griffith's wife Bertha Mann

Raymond Griffith in A DASH OF COURAGE (1916)

Raymond Griffith in A SCONDREL'S TOLL (1916)

Raymond Griffith in HIS HIDDEN TALENT (1917)

Raymond Griffith in AN AERIAL JOYRIDE (1917)

Raymond Griffith in HIS DOUBLE LIFE (1918)

Raymond Griffith in THEIR NEIGHBOR'S BABY (1918)

Raymond Griffith in THE FOLLIES GIRL (1919)

Raymond Griffith in THE DAY OF FAITH (1923)

Raymond Griffith in THE ETERNAL THREE (1923)

Raymond Griffith in RED LIGHTS (1923)

Raymond Griffith in WHITE TIGER (1923)

Raymond Griffith in CAUGHT IN THE END (1917)

Raymond Griffith in CHANGING HUSBANDS (1924)

Raymond Griffith in THE DAWN OF TOMORROW (1924)

Raymond Griffith in NELLIE, THE BEAUTIFUL CLOAK MODEL (1924)

Raymond Griffith in LILY OF THE DUST (1924)

Raymond Griffith in OPEN ALL NIGHT (1924)

Advertising for MISS BLUEBEARD (1925)

Raymond Griffith in FORTY WINKS (1925)

Raymond Griffith in FINE CLOTHES (1925)

Raymond Griffith in THE NIGHT CLUB (1925)

Raymond Griffith in PATHS TO PARADISE (1925)

Raymond Griffith in A REGULAR FELLOW (1925)

Raymond Griffith in the unreleased GET OFF THE EARTH (1926)

Raymond Griffith in WET PAINT (1926)

Raymond Griffith in HANDS UP! (1926)

Raymond Griffith in YOU'D BE SURPRISED (1926)

Raymond Griffith in WEDDING BILL$ (1927)

Raymond Griffith in TIME TO LOVE (1927)

Raymond Griffith in TRENT'S LAST CASE (1929)

Raymond Griffith in THE SLEEPING PORCH (1929)

Raymond Griffith in ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (1930)

Raymond Griffith as associate producer in GIRLS' DORMITORY (1936)

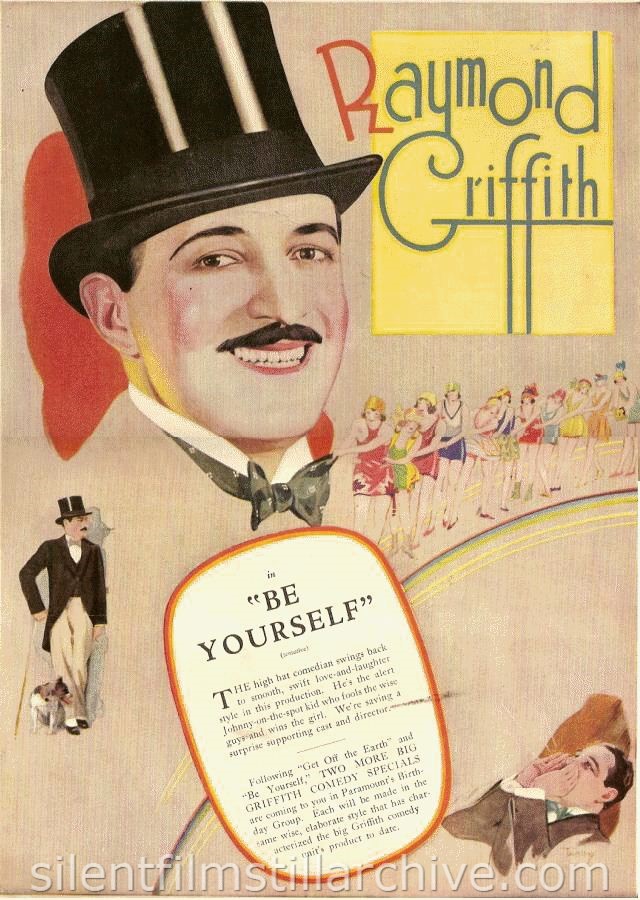

Be Yourself was announced by never produced by Paramount.

in "BE YOURSELF" (tentative)

THE high hat comedian swings back to smooth, swift love-and-laughter

style in this production. He's the alert Johnny-on-the-spot kid who

fools the wise guys and wins the girl. We're saving a surprise

supporting case and director.

Following "Get Off the Earth" and "Be Yourself," TWO MORE BIG GRIFFITH COMEDY SPECIALS are coming to you in Paramount's Birthday Group. Each will be made in the same wise, elaborate style that has characterized the big Griffith comedy unit's product to date.

Books

A-Z of Silent Film Comedy by Glenn Mitchell, pp. 107-108.

The Silent Clowns by Walter Kerr, chapter 31.

The Great Movie Comedians, by Leonard Maltin, chapter 8.

Last Modified August 15, 2024.